The Strategic Incentives Behind Verizon and AT&T’s Pricing Power, Investment, and Network Quality

By: Advait Sunil

Edited by: Seungho Choi

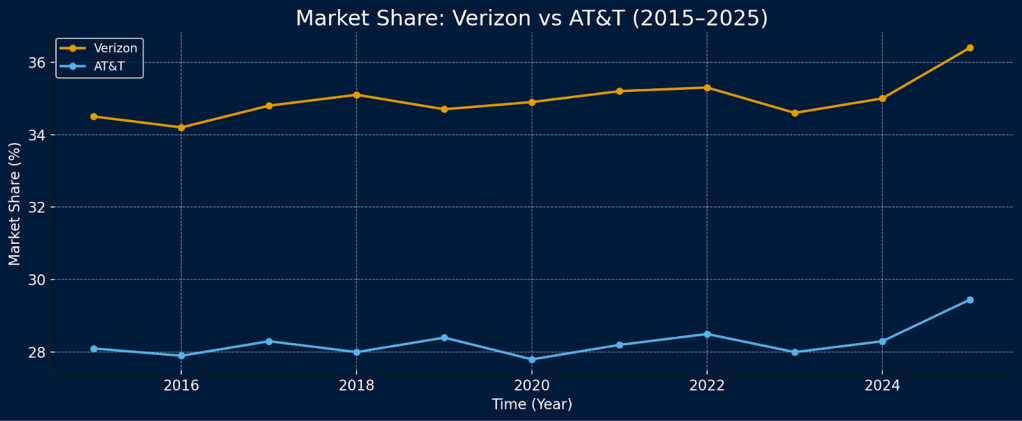

In 2025, American telecommunications consumers live in a paradox. They rely on their mobile and broadband connections more than ever, yet two of the country’s dominant telecom giants with over 50% of the market share — AT&T and Verizon — offer a choice that increasingly feels like no choice at all. While T-Mobile commands a larger market share than AT&T (33.07% of T-Mobile vs 29.45% of AT&T), AT&T and Verizon represent the clearest extremes in pricing and investment strategy. T-Mobile, while significant, closely mirrors Verizon’s quasi-premium market positioning and convergent monetization approach, making AT&T a more distinct counterpoint and making them ideal case studies for evaluating the price-quality trade-offs shaping consumer welfare. In a capital-intensive industry where 5G, fiber, and AI investments are reshaping cost structures and business models, these firms show managerial incentives promising affordability or innovation. Few experience both.

Verizon AT&T

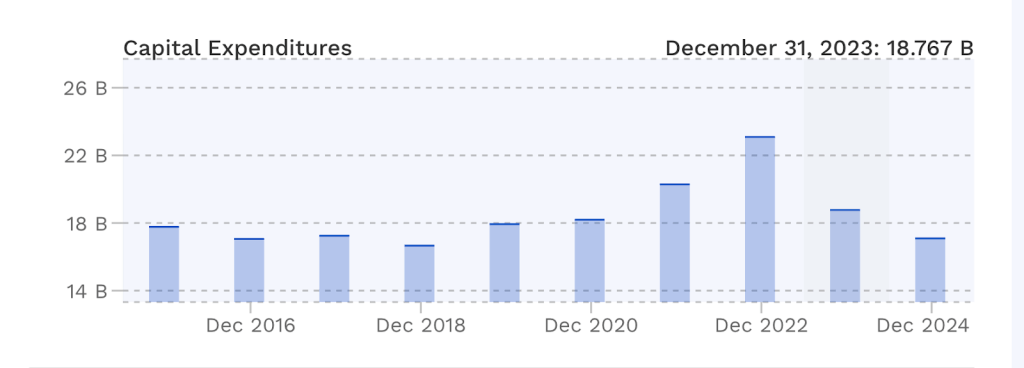

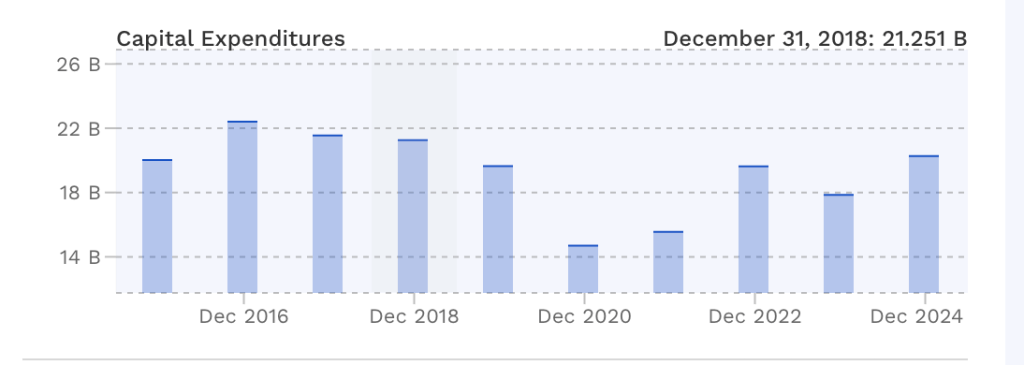

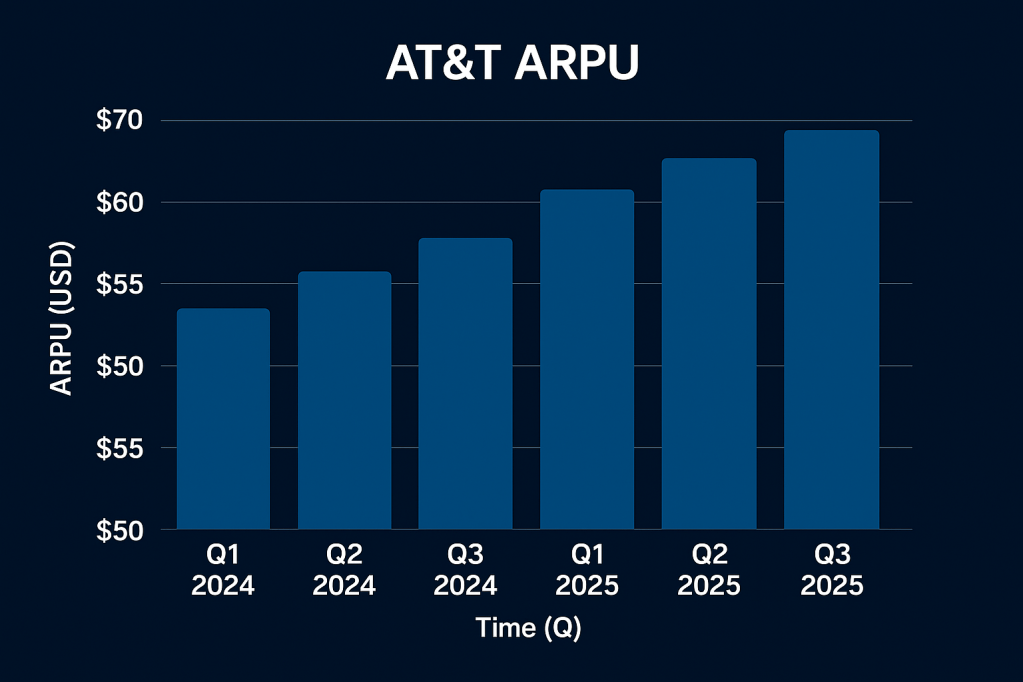

Static efficiency asks whether prices reflect demand elasticities and marginal costs today — i.e., whether consumers can access affordable connectivity. On the other hand, dynamic efficiency asks whether pricing and margins sustain innovation and investment over time or even reduce future costs (5G densification, fiber roll-out, and AI-driven network automation). In capital-intensive industries like telecoms, fixed costs (such as fiber deployment and required spectrum investments) dominate, and operators face persistent margin pressure as they balance these rising capex demands with pricing pressures. Thus, for AT&T, where executives are rewarded primarily for subscriber growth, managers are forced to opt for penetration pricing at the behest of executives, alongside promotions and bundle discounts — even if that compresses margins. But when incentives are tied to Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization margins, average revenue per account (also known as average revenue per user) and capital efficiency, managers at Verizon are rewarded for premium tiers, selective segmentation, and cost discipline — thus creating a two-tier market.

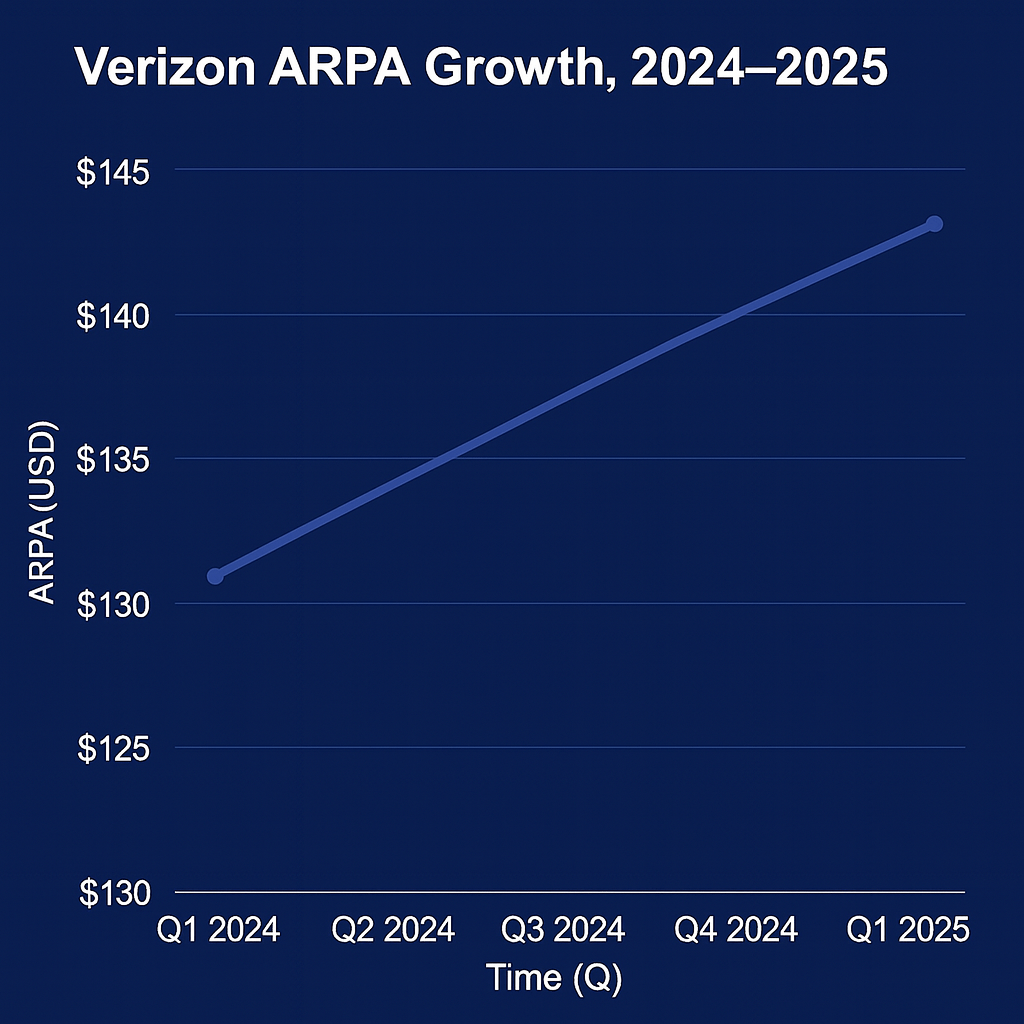

Verizon has long pursued a strategy of quality-driven differentiation. Historically, it invested heavily in building its brand reputation, then marketed that reliability aggressively, most famously through the “Can you hear me now?” campaign that embedded reliability into its brand identity. Even now, Verizon’s 2025 3Q earnings confirm the premium model. Verizon reported wireless service revenue reached $21.0 billion — up 2.1% year-over-year, with consumer wireless postpaid ARPA at $147.91 — rising 2.0% despite missing the forecast on net subscriber addition. Churn remains low, particularly on postpaid plans (0.91%), suggesting a relatively inelastic high-value customer base, with Investing noting “15 percent of its wireless service revenue comes from discounted streaming services with a growth rate of double‑digits.” As a result, Verizon’s pricing power is preserved through brand and customer stickiness rather than discounting. Circles echoes that sentiment, highlighting that “[w]ith market saturation and rising competition from MSOs and MVNOs, operators must shift from broad-based bundling to specialized digital sub-brands targeting profitable micro-segments.” Hence, these firms resort to perks and segmentation rather than across-the-board price cuts.

Taken together, Verizon’s strategy is a vertical-differentiation story: by convincing consumers that quality is superior, it can charge higher markups to less elastic, higher-income segments. In fact, “Verizon lost more monthly bill-paying wireless subscribers than analysts expected over the last eight months, due in part to price hikes, in part due to tariffs, and heightened competition from rivals’ promotions.” Consequently, in the short run, these customers who highly value reliability and can afford the premiums benefit, enjoy a high consumer surplus. But over the medium term, as we can already see, rising ARPA and selective segmentation will squeeze middle-income and budget-constrained users out of the premium tier in place of only those who are willing and able to pay. “In this same period, AT&T’s subscriber growth ‘stomped’ Verizon’s, as price-sensitive consumers gravitated toward cheaper alternatives.” What ensues, over the long run, is that this premium oligopoly segment of a limited but wealthy customer base subsidizes Verizon’s high investment, which is an excludable and rivalrous service. But the middle and low-income consumers will be stuck with inferior and less innovative options in a market where network coverage is a highly inelastic good given today’s digital world. This includes both independent low-cost mobile carriers and stripped-down plans or digital sub-brands owned by the telecom giants themselves, such as Cricket (AT&T), Visible (Verizon), and Boost (Dish Network). These options trade off innovation (e.g., slower rollout of 5G features, reduced access to premium customer support, or deprioritized data speeds), which results in a lack of investment in next-gen infrastructure owing to turbulent price equalization.

In contrast, AT&T’s modern strategy looks almost inverted. Over the past decade, the company continued its dominance through major acquisitions like DirecTV (2015) and Time Warner (2018) that expanded its vertical integration. But today, its new service guarantee appears to be a sales-maximizing strategy, as AT&T’s website said it emphasized “subscriber growth, fiber build-out and higher free cash flow, with capital expenditures targeting cost savings.” Normally, high fixed costs and low marginal costs result in firms rationally pursuing low prices to rapidly increase the subscriber base, and then spread fixed costs over a larger volume. However, when bonuses are tied heavily to subscriber metrics, there is a risk of underpricing below long-run sustainable levels, especially if rivals do not match discounts. In the short run, AT&T’s approach clearly improves access and affordability, raising static consumer surplus, particularly for lower- and middle-income users who might otherwise struggle with premium pricing. But the weakness appears in the medium term. When discounts compress margins faster than cost savings or efficiency gains materialise, investment budgets come under pressure. Outside dense, high-ARPU urban markets, such a pattern has already caused the Communications Workers of America Union to file a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission that “AT&T’s ‘mobile first’ proposal would put rural communities last, with lower quality and less reliable connectivity options.”

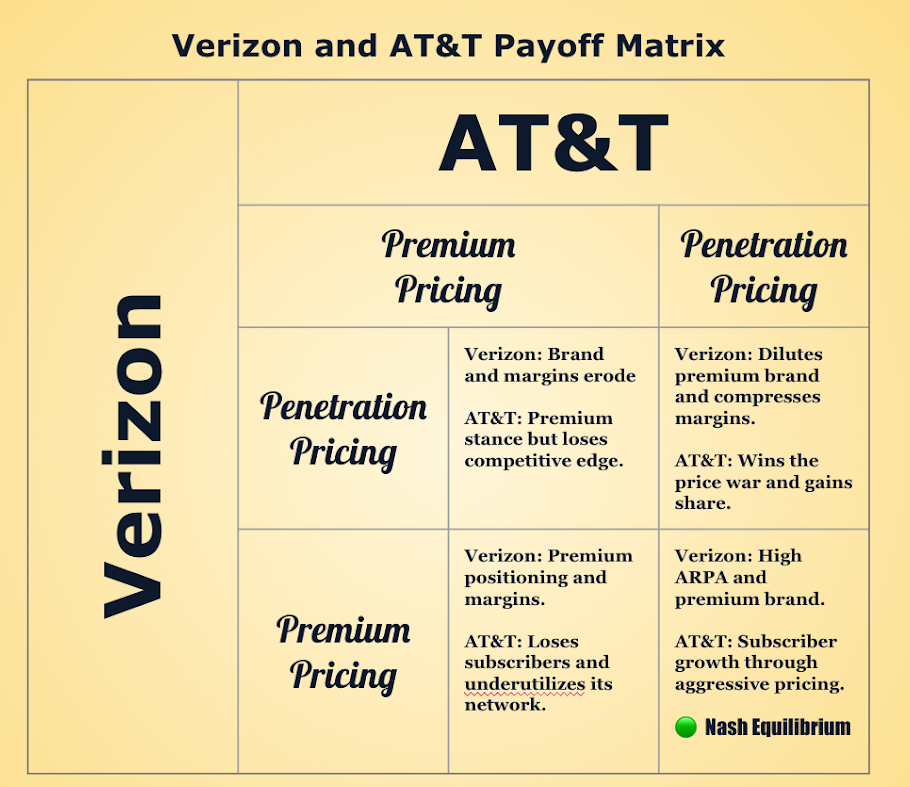

If we model AT&T and Verizon as differentiated Bertrand competitors, with brand and network quality acting as sources of product differentiation, we would see how a Nash equilibrium emerges where neither can unilaterally improve profits by changing price. Each firm’s strategy is the best response to the other. If Verizon cut prices to chase AT&T’s volume, it would erode its premium brand and margin advantage. If AT&T matched Verizon’s ARPA by raising prices and trimming promotions, it would lose the subscriber gains that justify its investment plan. The result is a Nash equilibrium: neither firm can unilaterally deviate for a higher profit, yet consumer surplus is not maximised. This is not just in the US telecoms market. India’s mobile market, for example, has seen extremely low data prices driven by high competition and rapid 5G adoption, boosting short-run affordability and usage, but placing severe financial strain on weaker operators — limiting their capacity to invest and innovate. Conversely, the U.S. skews toward high prices and selective innovation, and the lack of incentive-aligned regulation results in both markets settling into equilibria where either affordability or innovation dominates, but not sustainably. The FCC, however, has not even defined a latency or a reliability threshold for a mobile or broadband service.

To break this false choice, the FCC needs to implement a transparent tiered-pricing and premium rate-of-return ceiling, as it has on other natural monopolies such as electricity, gas, and water. This would mark a fixed fee that only allows Verizon and AT&T to cover their operating costs, depreciation, and a regulated percentage of profit on capital invested. By utilizing the extra income from tariffs, the government could allocate increased discretionary funds to the telecom sector to cover inspection costs. And while they can only estimate the marginal cost plus essential infrastructure amortization, the purpose is twofold. It would prevent unsustainably high prices that undercut long-run investment, mainly capex, while also avoiding a “race to the bottom” in which penetration pricing leads to under-recovery of fixed costs. Higher margins should only be permitted to firms that have verified incremental innovation investment (e.g., new spectrum deployment, fiber build-out, rural 5G coverage, or open-RAN projects beyond baseline obligations), which would mostly address the principal-agent problem and create a separating equilibrium.

And as we are in a natural oligopoly situation, Ramsey pricing takes center stage, where we should deviate from marginal cost in proportion to the inverse of demand elasticity, with telecom markets bearing higher markups. That is to account for only the portion of revenue equal to a firm’s transfer earnings, while any pricing above that level reflects economic rent that must be justified by elasticity-based efficiency or genuine innovation, which challenges Verizon’s pricing. At the same time, this prevents excessive markups and sub-marginal underpricing in AT&T’s aggressive penetration pricing. Regulators would then be able to assess whether pricing tiers reflect efficient elasticity-based discrimination or whether they impose regressive cross-subsidies, showing how innovation today shifts future cost curves through economies of scale, and how innovation and affordability co-exist rather than exist as a trade-off. Nonetheless, this does come at the risk of firms pursuing superficial or low-impact innovation projects. So non-partisan auditors must routinely check whether firms are also reclassifying routine maintenance as innovation, especially after the 2001 Enron Scandal.

Taken together, the strategies of Verizon and AT&T reveal a deeper structural tension within American telecommunications: consumers must choose between premium reliability at increasingly exclusionary prices or accessible plans whose long-run sustainability is uncertain. Verizon’s margin-driven, quality-centric model secures innovation but narrows affordability. AT&T’s subscriber-driven, discount-heavy approach expands access but risks undermining future investment capacity. While there are loopholes to bypass regulatory tools, rate-of-return ceilings, elasticity-aligned Ramsey pricing, and stricter innovation audits offer a way to resolve this false trade-off, aligning firm incentives with both affordability and continued technological progress. And only by redesigning these incentives can policymakers prevent the market from drifting into an equilibrium where either innovation or accessibility dominates at the expense of the other. Still, stable investment and a shift from second-degree to first-degree price discrimination could present a path toward the kind of market the U.S. has long lacked: one where innovation lowers prices.

Leave a comment