Since 2022, the Central Bank of Russia has shifted from conventional inflation targeting to “constraint targeting,” a hybrid regime in which interest rates, capital controls and yuan-based foreign-exchange operations are used to defend the ruble and the external balance under sanctions.

Image Source: Agenzia Nova

By: Vladimir Gaberman

Edited by: Alex Oh

On the eve of the February 2022 Special Military Operation in Ukraine, the Central Bank of Russia operated a conventional inflation-targeting regime with a 4% target and what it described as a floating ruble, backed by about $630 billion in international reserves. In practice, a floating currency is one whose value is set mostly in foreign-exchange markets, without a legally fixed peg, although central banks still lean against large swings.

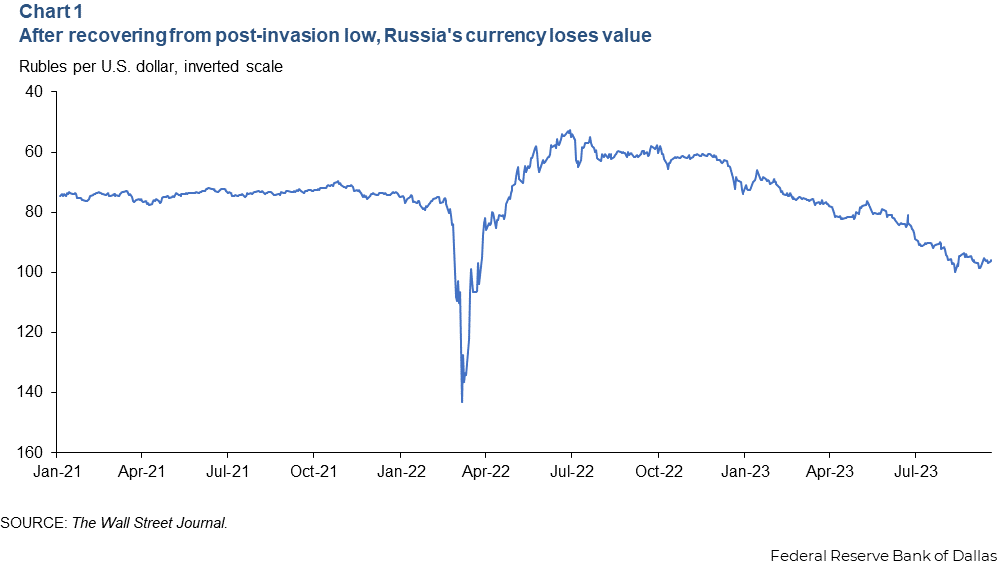

That arrangement effectively broke in late February 2022 when the United States, European Union and allies immobilized roughly half of Russia’s reserves, cutting usable buffers to about $300 billion. The ruble slid from the mid-70s per dollar in early February to well above 100 per dollar in early March. The CBR raised its key rate from 9.5% to 20% at an emergency meeting, imposed strict capital controls and ordered exporters to sell 80% of their foreign currency revenues on the domestic market. Residents faced tight limits on foreign-currency withdrawals and transfers abroad and nonresident investors were barred from selling Russian securities. At the same time, the authorities began to retool the fiscal “budget rule,” shifting planned foreign-exchange operations from dollars and euros into Chinese yuan to reduce seizure risk. In effect, U.S. and EU sanctions that targeted reserves and payment channels forced the CBR to move from clean inflation targeting toward a regime that openly targets the external financing constraint.

Post-2022 behavior, therefore, looks less like textbook inflation targeting and more like what can be called constraint targeting. In this regime, the central bank openly subordinates strict inflation control to binding external and exchange-rate constraints. External financing conditions and the ruble’s level became binding policy variables, and the CBR’s reaction function appears to have expanded from a narrow focus on the domestic inflation gap to a state-contingent rule that responds directly to the exchange rate and the balance of payments.

Under sanctions, the CBR and the Russian state have relied on three main instruments: the policy rate, capital and foreign exchange controls, and FX operations built around the fiscal rule. After the key rate jumped to 20% in February 2022, the CBR cut rates as panic subsided and the ruble appreciated, bringing the policy rate back into single digits by late 2022. That easing stopped once the ruble began to weaken again in 2023. As export revenues fell and the ruble moved toward triple-digit territory, the CBR reversed course and raised the key rate first to 8.5%, then to 12% and later to the mid-teens. In August 2023, the bank singled out ruble depreciation and a deteriorating trade balance as the main sources of inflation risk, a marked shift from prewar language that had centered on the domestic forecast. By the end of 2023, the key rate was at 16% and remained there into mid-2024. As inflation and the budget deficit climbed, the CBR increased the rate again to 18% in July 2024, 19% in September and 21% in October, its highest level since the early 2000s. The bank then held 21% into early 2025 despite strong political pressure, before beginning to cut gradually to 20% and 18% as inflation started to ease.

Capital controls and FX-surrender rules operate alongside the policy rate. The initial requirement for exporters to surrender 80% of foreign-exchange revenues, combined with bans on many private capital outflows, trapped foreign-currency earnings onshore in 2022. As the ruble overshot to unusually strong levels in mid-2022, authorities loosened some of these constraints, cutting the surrender ratio and easing transfer limits. When external conditions deteriorated again, controls were tightened. In October 2023, facing a ruble above 100 per dollar and a much narrower current account surplus, the Kremlin reintroduced a de facto surrender rule for selected commodity exporters, obliging them to repatriate 80% of foreign-exchange receipts and sell most of that into rubles on a fixed timetable. The requirement was later reduced to 60% in June 2024 as pressure on the currency briefly eased, then to 40% in July, confirming that capital controls have become a recurrent, state-contingent tool rather than a one-off emergency measure.

The third leg of the regime is the repurposing of FX operations under the fiscal rule. During the 2010s, the finance ministry routinely bought or sold foreign currency, typically dollars and euros, to sterilize oil-revenue swings. After sanctions froze those reserve currencies, the ministry announced that any resumed operations would use yuan as the intervention asset instead. When oil prices later recovered, the ministry resumed modest yuan purchases, but in August 2023, as those purchases added to ruble pressure, it halted FX buying and the CBR signaled that exchange-rate stability would take precedence over mechanical adherence to the rule. By late 2024, as the ruble again came under heavy pressure, the central bank suspended FX purchases in full for the remainder of the year in order to avoid adding to depreciation.

The joint behavior of the ruble, the external accounts, interest rates and inflation points toward a reaction function that weighs external stability heavily. The ruble sold off from roughly 75 to more than 100 per dollar at the onset of sanctions. After the 20% rate hike and tight controls, trapped export earnings and a collapse in imports produced a record current account surplus of more than 10% of GDP in 2022 and the ruble appreciated into the 50s per dollar in mid-2022, stronger than prewar levels. As oil-price discounts widened, export volumes fell and imports rerouted through “friendly” jurisdictions, the current account surplus shrank sharply. By mid-2023, the surplus was only a fraction of its 2022 level and the ruble slid back through the 80s and 90s, breaching 100 per dollar in August. The pattern repeated in 2024. New US sanctions on Gazprombank and continued military spending pushed the ruble to around 110–113 per dollar in November 2024, its weakest level since the first weeks of the war, and the current account moved toward balance. The CBR’s response was to halt FX purchases, raise the key rate to 21% and signal a willingness to keep policy tight until inflation and expectations moderated. By 2025, as high interest rates and weaker domestic demand curbed imports and inflation, the ruble regained part of its late-2024 losses and traded back below triple-digit levels, even as the current account slipped toward small monthly surpluses and deficits.

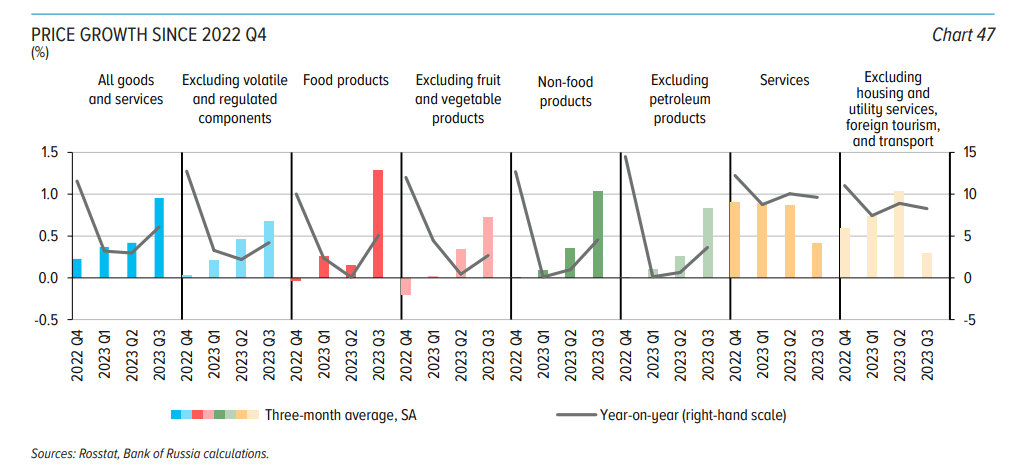

The behavior of inflation and interest rates reinforces this picture. Consumer price inflation peaked around the high teens year over year in spring 2022, then declined toward 12% by year-end as the ruble recovered and demand softened. Inflation slowed further in early 2023, briefly dipping close to the 4% target on base-effect grounds, but accelerated again as the ruble weakened and imported input costs rose. Through 2024, inflation fluctuated around 8 to 10%, driven by war-related fiscal expansion and rising wages in defense-linked industries. The CBR’s communications during the 2023–24 hiking cycle emphasized depreciation pass-through and the risk that a weaker ruble and loose fiscal policy would entrench elevated inflation expectations. The pattern is inflation persistently above target but far from hyperinflation, consistent with a “defend the currency, tolerate moderate overshoot” strategy.

Domestic financial markets have also become segmented. Yields on Russian OFZ government bonds spiked above 15% when trading reopened in 2022, then fell back as the CBR cut rates and the state and large banks absorbed supply. Nonresident holdings, which had been roughly a third of the OFZ stock, fell to single digits as foreign investors were frozen in place or exited through distressed channels. Russian sovereign Eurobonds, which embed default and sanctions risk, traded at deep discounts to face value, while domestic yields increasingly reflected the CBR’s policy stance under capital controls rather than global risk pricing. High deposit rates moved households’ savings into the banking system in record volumes, while corporate borrowing became more dependent on state-linked banks and subsidized credit programs. This combination amounts to financial repression that gives the central bank more room to move rates in defense of the ruble, but at the cost of weaker private investment.

The CBR’s behavior under sanctions is consistent with open-economy macroeconomic theory on sudden stops and with the empirical literature on fear of floating. In sudden-stop settings, a loss of external financing and a jump in the domestic risk premium make the exchange rate a key state variable. The central bank cares about the path of the exchange rate not only because of price pass-through, but also because a large depreciation can damage balance sheets and undermine the payments system. Sanctions and reserve freezes created a sudden stop by fiat rather than by investor panic, but the constraints looked similar: limited external borrowing, impaired reserves and heightened uncertainty about access to foreign currency. Guillermo Calvo and Carmen Reinhart’s work on fear of floating, along with other contemporaries on emerging-market policy rules, show that many central banks with formal floats move interest rates and intervene heavily whenever the exchange rate crosses implicit thresholds. Russia now fits that pattern. The CBR has kept the language of inflation targeting and a floating ruble, yet post-2022 actions reveal a much lower tolerance for exchange-rate variation than in the pre-sanctions period. The emergency hikes of 2022, the 2023–24 tightening cycle to 21%, the suspension of FX purchases and the on-again, off-again use of surrender mandates all respond to ruble volatility and current-account swings.

Tinbergen’s rule suggests that multiple objectives require multiple instruments. Once free capital mobility was sacrificed, Russia had more scope to combine tools. The policy rate now serves both as an inflation and as a currency-defense instrument, while capital controls, FX regulation and fiscal-rule operations provide additional levers for managing the external constraint. Russia’s experience is consistent with other crises in which capital controls and administrative measures were used to stabilize exchange rates and banking systems when reserves and credibility were strained, although in this case, the trigger was a geopolitical shock rather than a classic capital-flow reversal. The regime is unusual in its combination of commodity dependence, partial insulation from foreign-currency debt and the legal shock of reserve seizure, but the logic of responding to a binding external constraint with a hybrid monetary framework is familiar.

The revealed tradeoff in 2022–2025 is clear. On one side, the CBR and the Russian state avoided a classic balance-of-payments and banking crisis. The ruble’s initial collapse was reversed, domestic payments continued and banks remained liquid and solvent despite severe sanctions. GDP also contracted by much less than early forecasts of a double-digit decline and even grew again in 2023–24, aided by war-related demand. On the other hand, the medium-term costs are substantial. Inflation has persistently stayed above the 4% target, generally in a mid-single to low-double-digit range, and expectations have become sticky. Policy rates in the mid-teens to low-twenties depress credit and investment, producing a low-growth, high-inflation equilibrium. Capital controls and market segmentation shield the domestic system from external runs, but they also impede efficient allocation and make the economy more dependent on state-directed finance.

There is a credibility cost as well. De jure, the CBR retains an inflation-targeting mandate with a floating ruble and a 4% target. De facto, its behavior under sanctions reveals a broader mandate that includes exchange-rate stability and external viability. When those goals conflict with a rapid return of inflation to target, the bank has repeatedly chosen to defend the ruble and the payments system. Private agents are likely to internalize this shift. They can observe that the CBR’s reaction function now responds not only to a domestic inflation gap, but also to a ruble gap and an external-balance gap, using a broadened toolkit that includes capital controls and FX operations in yuan. This wedge between de jure and de facto mandates may anchor expectations at a permanently higher inflation rate than 4%, reflecting a perceived ruble-defense option embedded in policy. As long as sanctions keep external financing and reserve access constrained, this constraint-targeting regime is likely to define Russian monetary and exchange-rate policy.

Leave a comment