We have seen rapid expansion of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet to combat the Covid-19 crisis, but since 2022, the Fed has shifted to quantitative tightening to normalize the economy. Now, three years later, we observe the successes of quantitative tightening along with incoming challenges that threaten a smooth landing.

Image Source: Tim Evanson

Written by Emily Yan

Edited by Hiya Kumar

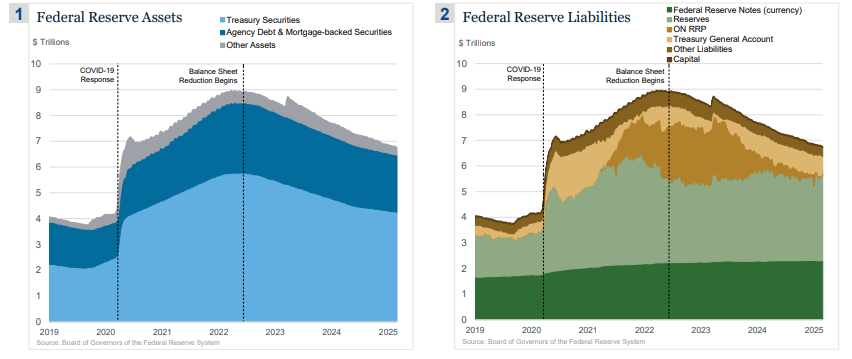

The pandemic marked an all-time high in government expenditure as the federal government rushed to provide stimulus checks to households and businesses through the CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act) while implementing borrowing programs. Added together, federal spending in response to Covid-19 totalled to around $4.6 trillion. To support these massive spending programs and stimulate the economy, the Federal Reserve was fast in resuming quantitative easing, as it had done a decade ago during the 2008 financial crisis. This led to rapid expansions in the Fed’s balance sheet which climbed to a peak of $8.9 trillion in March 2022—a $4 trillion increase from early 2020’s size of $4.2 trillion.

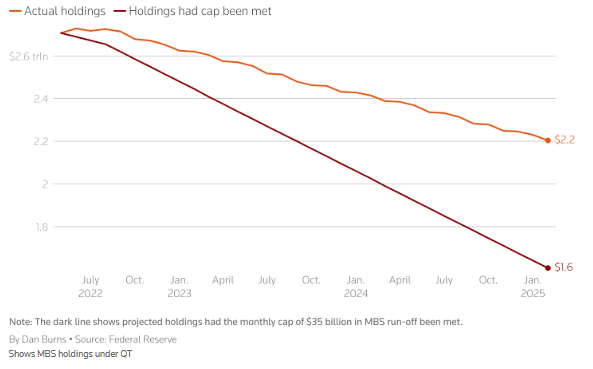

As the world pushed to return to pre-pandemic normal, similar discussions were unfolding within the Fed. Inflation was climbing steeply with the CPI rising as high as 9.1% in June 2022. In the same month, the Fed began implementing quantitative tightening (QT) alongside interest rate hikes to withdraw the excess liquidity it had injected into the financial system during the height of the pandemic. The plan was to cap Treasury security reinvestments at $30 billion per month and then increase it to $60 billion per month three months later. In addition, mortgage-backed securities (MBS) would be capped at $17.5 billion per month, raising to $35 billion over the same period – mirroring the approach for Treasuries. These runoff caps were explicitly specified because Treasuries and MBS are the primary assets on the Fed’s balance sheet and were the main securities the Fed bought during the pandemic to ensure liquidity and stability in their respective debt markets. As recorded in the 2022 Q1 Federal Reserve Banks Combined Quarterly Financial Report, Treasury securities accounted for around 67.34% of all Federal Reserve assets while MBS was the second largest, comprising 31.12%.

While hikes in the federal funds rate (FFR) had immediate effects which were reflected in financial markets, QT impacts were slower as it relates to the underlying demand within the Treasury and MBS markets. The combined effect of reducing excess liquidity and raising the FFR allowed the Fed to rein back inflation, which is one of the two mandates the central bank was founded to achieve. By not reinvesting portions of the returns, fewer reserves would remain in circulation, thereby slowing down the economy since financial institutions would have less excess reserves to actively invest. As of 2025, QT has successfully reduced the Fed’s balance sheet almost by half of the expansion that occurred between 2020 and mid-2022, with the pace of runoffs gradually easing down. Looking at the Federal Reserve Assets in Figure 1, it can be observed that the majority of reduction has come from Treasury securities, which have had a more successful runoff than MBS. Since mortgage rates have been high, a fall in demand for MBS would lead to a further decline in prices, in turn pushing up yields even more. Therefore, to maintain stability in the mortgage market, the Fed has been holding back on meeting its monthly reduction target as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Federal Reserve Assets and Liabilities

Figure 2: Mortgage-Backed Securities Runoff

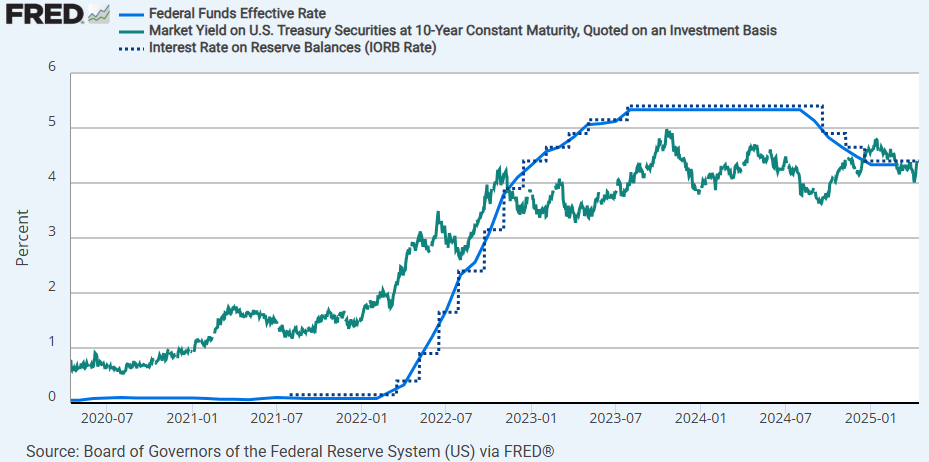

Despite its successes, the fight to ease out liquidity also created a historic flip within the Fed. For the first time since its creation in 1913, the central bank began incurring continuous operating losses when it raised interest rates above Treasury yields. The unrealized losses from the gap between the interest rate on reserve balances (IORB) and the market yield as shown in Figure 3 combined with losses due to low market value of MBS reached as high as $1.1 trillion by late September 2022.

Figure 3: Effective Federal Funds Rate vs. US Treasury Securities Market Yield

Additional note: The 10 year Treasury market yield is often used as an indicator of the overall market yield.

Although this massive amount was not completely realized, the Fed still reported a cumulative operating loss of $191.9 billion for 2023 and 2024. This has led to a halt in remittances to the US Treasury, which are transfers of net earnings to the Treasury General Account (TGA), and beginning of issuances of “deferred assets”. This accounting trick of negative liability allows the Federal Reserve to continue its operations in implementing monetary policy without interference. When the central bank resumes generating an operating profit, it will first use those earnings to pay down these “deferred assets” before sending any remittances to the Treasury.

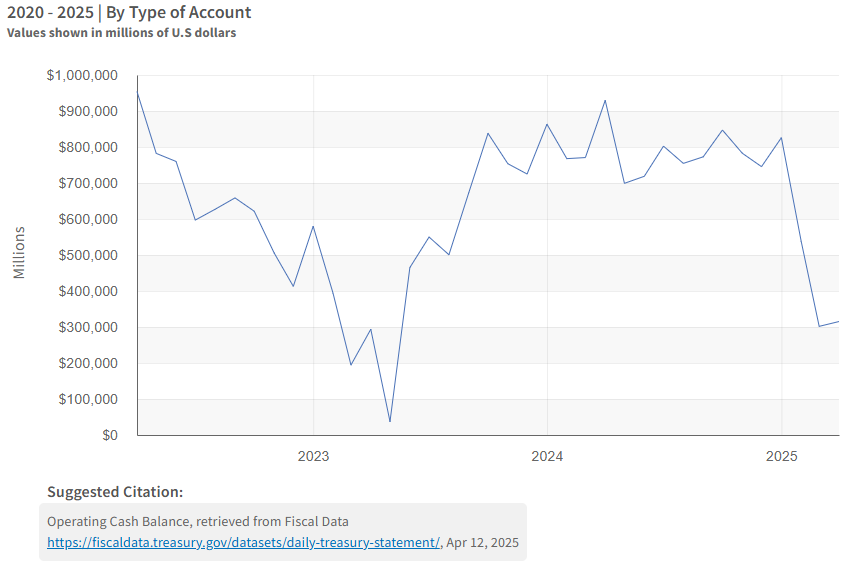

This was not a major issue during the pandemic when the debt limit was suspended. However, the recent reinstatement of the $36.1 trillion debt limit on January 2, 2025 has once again raised concerns about the Fed’s plan for QT, especially as the federal debt continues to hover above the limit set by Congress. To meet its obligations for Social Security and healthcare, the US government has been continuously drawing from the TGA, the balance of which has dropped to precariously low levels. The account held $704 billion when President Trump first took office on January 21, 2025 and has since dropped to $315 billion, as of April 2025.

Figure 4: Daily Treasury Statement (as of April 12, 2025)

As the Federal Reserve continues its fight to stabilize prices, remittances to the Treasury will likely not be available until it begins to run operating profits and pays off its large sum of $221 billion in deferred assets as of February 2025 – a situation not expected to resolve within a year or two. This increases pressure on the federal government to come to an agreement on the next steps as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the government will be unable to utilize “extraordinary measures” to borrow additional funds and will dry-out the TGA by August or September 2025. Both before a debt ceiling resolution and immediately after, the Fed will be facing many challenges.

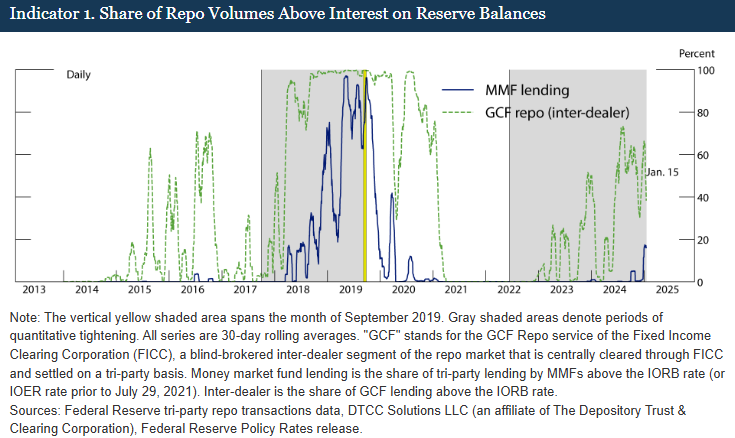

Drawing from the TGA injects extra liquidity into the financial system. “These higher reserve levels are ‘artificial’”, Roberto Perli, manager of the System Open Market Account, described in his speech to Money Marketeers of New York University on March 5, 2025. “They are driven by a temporary redistribution of Fed liabilities and are likely to quickly reverse.” Before the debt limit situation is resolved, the Fed will need to set its future monthly reinvestment cap taking this into account, which makes estimating reserve levels difficult. Perli also mentions that the TGA typically rebuilds quickly after a new debt limit is set, leading to a “rapid decline in our other liabilities”. The extraction of large amounts of reserves in an unusually short amount of time can easily shake up money markets given that the Fed has been gradually reducing liquidity in the financial system. There have recently been signs of reserve scarcity as the proportion of money market fund (MMF) repo lending at rates above IORB has risen, indicating that there is high immediate demand from banks for cash. This would not occur if banks have an abundant amount of reserves. If other indicators of low reserve levels begin blinking red, there will be major instability in the money market during the resolution of the debt limit problem unless the Federal Reserve reverses its previous actions and re-introduces liquidity.

Figure 5: Money Market Fund Repo lending above IORB

The importance of treading carefully cannot be overstated. Prior incidents such as the September 2019 Repo Crisis when a liquidity crunch led to an abrupt spike in overnight repo rates demonstrate the need for the Fed to flexibly inject liquidity into the money market. A debt limit resolution would most likely lead to a rise in the limit, leading to an influx in Treasury debt available as the federal government restores the TGA balance. This occurred back in June 2023 when the debt limit was suspended and the TGA was replenished with over $600 billion within four months. With QT reducing reserves, settlement of Treasury debt, and corporate tax payments due, a mismatch between demand and supply could once again lead to money market rates skyrocketing.

Despite some officials pushing for a halt to QT to ride out the storm, the volatile financial environment and pressures of a long-term, full-scale trade war in April indicate the necessity to continue. Although inflation reports over the past few months and the announcement of an optimistic drop of CPI to 2.8% as of April 2025 seem to paint a bright picture, these lagging indicators are unable to capture future volatility. It is expected that with tariffs in place, inflation will climb back up with projections of a 1-1.5% increase in 2025 according to JP Morgan Global Research. A survey released by the University of Michigan in April also reports that respondents’ inflation expectations have risen to 6.7%. In face of challenges such as tariffs and raised inflation expectations, maintaining price levels should remain the Federal Reserve’s primary goal and QT is key to ensuring the central bank has flexibility in implementing expansionary monetary policy when cracks emerge in the economy. In his speech on April 4, 2025, Chairman Jerome H. Powell also highlighted the Fed’s focus on price stability.

Only when a smooth landing is ensured can the Fed turn its focus to potential concerns surrounding US economic growth, which has been stagnating with growth rates falling behind interest rates. However, when inflation comes down, at what point do we transition away from QT? In its announcement on plans to reduce the size of the Fed’s balance sheet back in May 4, 2022, the Federal Open Market Committee introduced its target to “stop the decline in the size of the balance sheet when reserve balances are somewhat above the level it deemed consistent with ample reserves”. The outline of this goal is somewhat ambiguous and there has not been much information on what the Fed is specifically targeting beyond brief mentions that they are following market indicators to observe shifts in supply and demand for reserves in order to determine when a situation of “ample reserves” is reached.

In addition to the confusion caused by recent market volatilities, the ambiguity is most likely due to cautiousness in giving cues to financial markets, which have been restless for rate cuts and a halt to monetary tightening. Still, in the current economic environment, it seems unlikely that the Federal Reserve will switch-up their policy direction and the complete end of QT does not seem to be any time soon as we are only halfway to the normal size of the Fed’s balance sheet. However, a slow-down and enforcement of momentary pauses in runoffs are likely to be seen throughout 2025 as the ON RRP facility has reached a post-2021 low and the Fed turns its focus to maintaining money market stability. Until normalization is fully achieved, every day will continue to be a game of patience.

Leave a comment